Rebirth of Osiris. Two-part mural by Hanaa El Degham

Image information

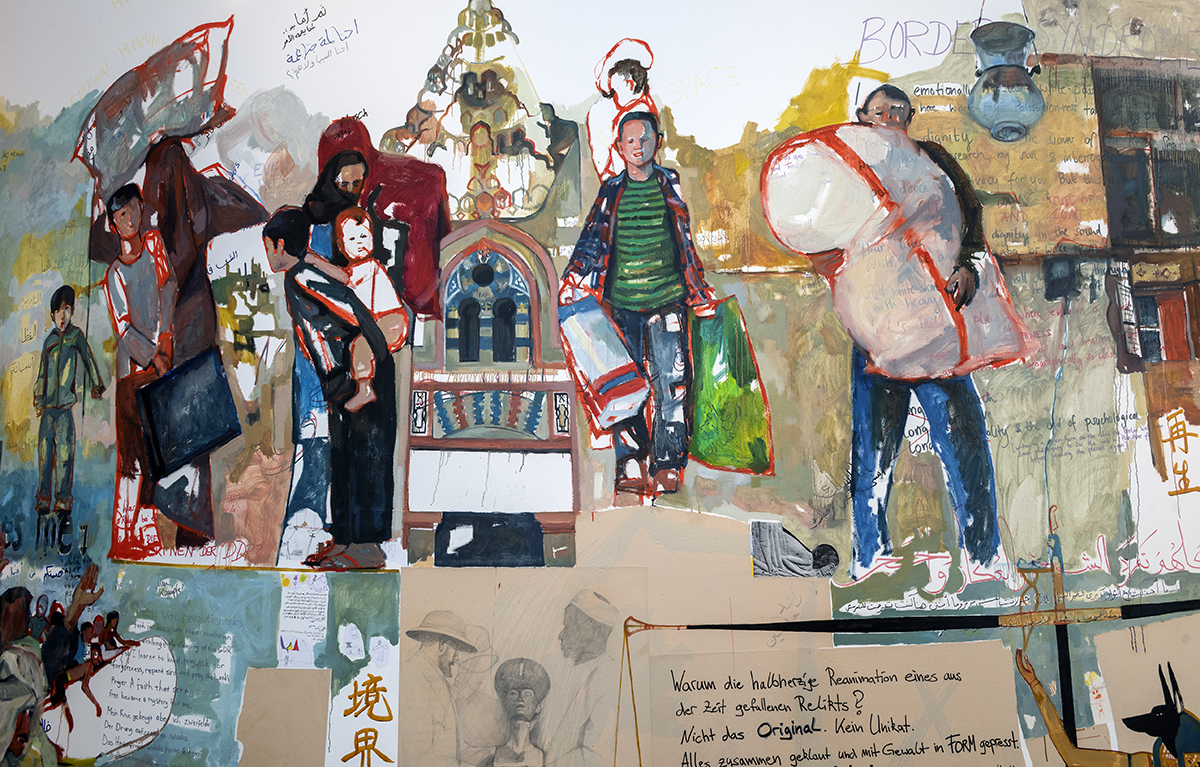

A large two-part mural dominates the Revolution room in the BERLIN GLOBAL exhibition. Nearly twenty metres long, it covers the outer side of two curved partition walls.

Created by Hanaa El Degham, the work is entitled Rebirth of Osiris. It is a combination of oil painting, egg tempera and collage on canvas. Intersecting scenes draw on motifs from ancient Egyptian mythology together with flying, fleeing, searching and dancing figures. The artist envisions a state of ‘revolution’ as movement, liberation and renewal.

Image information

The artist Hanaa El Dagham during her work on the mural “Rebirth of Osiris” in the permanent exhibition BERLIN GLOBAL

Hanaa El Degham has lived and worked in Berlin since 2008. When the Egyptian revolution began on the streets of Cairo in 2011, she wanted to be involved and travelled back to the city of her birth. There she worked with other artists near Tahrir Square, portraying the political uprising in gigantic murals as it unfolded.

For her mural in BERLIN GLOBAL, El Degham sought to bring the energy from street protests into the Humboldt Forum. In a first step, she invited numerous activists to reflect on what revolution meant to them personally, and to add their thoughts to the canvas in writing. These contributions served as the basis for El Degham’s painting.

El Degham composed the mural in large part from images collected from books and news sources or photos taken herself, translated large-scale into paintings on the wall. Over about two months, she painted, layered and collaged the canvas surfaces. She allowed the images to build on each other, coming together like a puzzle. For El Degham this process was a way to approach the space and her task step by step, with intention. The multitude of voices, movement, and the unfinished character of the work are thus key elements of the mural, like they are of a revolution itself.

Focusing on seven scenes, Hanaa El Degham guides viewers through her mural and discusses her artistic process.

Image information

(1) “The mural begins at the foot of a man who is bending over something. Originally it was a man searching in a rubbish bin for food. I transform him here into someone looking into a well – specifically, a well of knowledge. The ‘well’ in this case is a person, a dervish: a source of wisdom, healing and enlightenment. The man looks through this person and sees what is happening in the world; he sees the scenes of the painting that follow. In painting this part I was thinking about the game Sandok el Donia, which you see sometimes on the streets of Egyptian cities. A person walks around with this device, a metal box, and you pay to look inside and see images of past events. Something like a miniature kaiserpanorama.”

Image information

(2) “On the lower lefthand part of the canvas is a group of Sufis dancing in front of a boat carrying Africans on their way to Europe. This scene developed on site. I wanted the painting to include painful, heavy topics, but also different strategies of self-determination. Despite all the hardships people face, they find ways to break free from external conditions and find joy. The Sufis are one of the most impoverished groups in Egypt, but they find ways to create spaces of freedom in a trance, by dancing.”

Image information

(3) “The scene in the upper middle part of the mural evokes another aspect of simultaneity. In the background is a very beautiful mosque, in the foreground a line of refugees carrying their possessions out onto the street. Even people who flee come from rich cultural traditions, and they carry that history with them. Do they know they will arrive in another country where they won’t be understood or valued? It was important to me to counter the simplistic victim narrative of ‘poor and desolate’. Many people wonder where to find ‘the revolution’ in the mural. I respond by asking them what they expect a ‘revolution’ to look like: people on the streets with their fists in the air? Battles? What’s important to me is what brings people to this point –how unfair or unbearable everyday life can be for many of them. Revolution means destruction – destroying the old. That includes pain, loss, chaos and flight, until conditions change. When people ask whether I’m disappointed in the Egyptian revolution I have to say no, I’m not. People are disappointed when they expect things to happen right away. But how can we suddenly change structures that have existed for ages? I am glad the revolution happened because it opened our eyes. We need to ask ourselves why we went along with the existing power relations for so long.”

Image information

(4) “At the top left of the mural, Osiris sits next to his wife Isis and her sister Nephthys, in front of the flying eye, Horus, the protector. The story goes like this: Osiris rules Egypt and is considered very just. Seth, his brother, wants to take power and kills Osiris, dismembers him, and scatters the parts of his body throughout the land. He rules very unjustly. Isis gathers the parts of Osiris’ body so that she can become pregnant from him. Osiris doesn’t really come back to life, but becomes the god of the underworld. Isis gives birth to Horus, who loses his eye in a fight with his uncle. With his remaining eye, however, Horus sees truth in its entirety and searches for justice. This story contains ‘good’ and ‘evil’, but the point is that both are always there. We cannot drive ‘evil’ away, but instead need to find ways of dealing with it. I brought the myth of Osiris into the mural to illuminate human suffering, the absence of justice, the spread of corruption, and the disappearance of ancient Egyptian moral laws. In ancient Egypt symbolism was hugely important. I called Osiris into the painting so we could view my work together, so he could help me put everything into perspective.”

Image information

(5) “The second half of the Osiris scene shows the scales from the court of the dead. In ancient Egyptian mythology, when a person dies their heart is weighed against a feather. Anubis, the jackal-headed god, presides over the process. If the heart is lighter, then the person was good. If the heart is heavier, then the person was unjust and the heart is eaten by Ammit, a hybrid crocodile-lion-hippopotamus. A man is bowing down to the right of the scales. Is it a gesture of humility or is he asking for forgiveness? Osiris watches from a distance and awaits the judgment. Next to the heart is a text referring to the Humboldt Forum. Many people who contributed to the painting first had to overcome their reservations about the institution. Some of them decided to write about it. I linked the text about the Humboldt Forum with this image of the scales to show in visual terms how participants were weighing their thoughts. The Egyptian Book of the Dead also integrates images and text, and I wanted to reference that as well. I work on multiple levels at the same time: visually, symbolically, and with the overall message. I found it interesting to combine everything here – to bring in ancient elements and ask what they can tell us about the present.”

Image information

(6) “Here we are standing in front of the second half of the mural. Boys and girls are flying without wings, merging with the movement and joining the ranks of the revolutionaries. Flight without wings stands for a lightness that defies the laws of nature and embodies the soul’s attainment of a state of exultation and celebration. One of the starting points for the mural was the divide between destruction and reconstruction. In the first part everything is difficult; the scenes are very heavy; the people are on the ground. Here in the second half they lose this heaviness. The flying figures are based on youth in Gaza, who use parkour to free themselves from the confines of their environment. They have decided: ‘We want more lightness!’ ‘We’re flying!’ ‘We choose to see the world from a birds-eye perspective.’ They are part of the revolution. It’s not a demonstration but a carnival. I live in the stories that I paint. The images free my emotions, and I seek this lightness myself. This part of the mural also contains a scene that could belong to the other half. Arms and hands reach out of a train window and hold a person in the air – the person wants to go with them but doesn’t fit in the train. Hopelessness, but also solidarity.”

Image information

(7) “Toward the right end of the mural, a girl embodying the form of Ra, the sun god, is sitting on a swing. She turns away from the events and looks forward. She sends her rays from the sun disc into the land of Kemet (Egypt), which means ‘black earth’. The girl is rooted in Egypt, on an old map. The ground contains her history. But everything else is open, the canvas in front of her is white. She looks forward and thinks: ‘I know the future will bring hardships, but I will determine my own course. I will follow my own inner compass, my feelings and my thoughts.”

One object, Many questions: “Rebirth of Osiris”

In conversation with Sophie Eliot, a member of staff at the Stadtmuseum Berlin specializing in outreach, and visitors, artist Hanaa El Degham explained the background to her interactive artwork (May 25, 2022) WATCH VIDEO