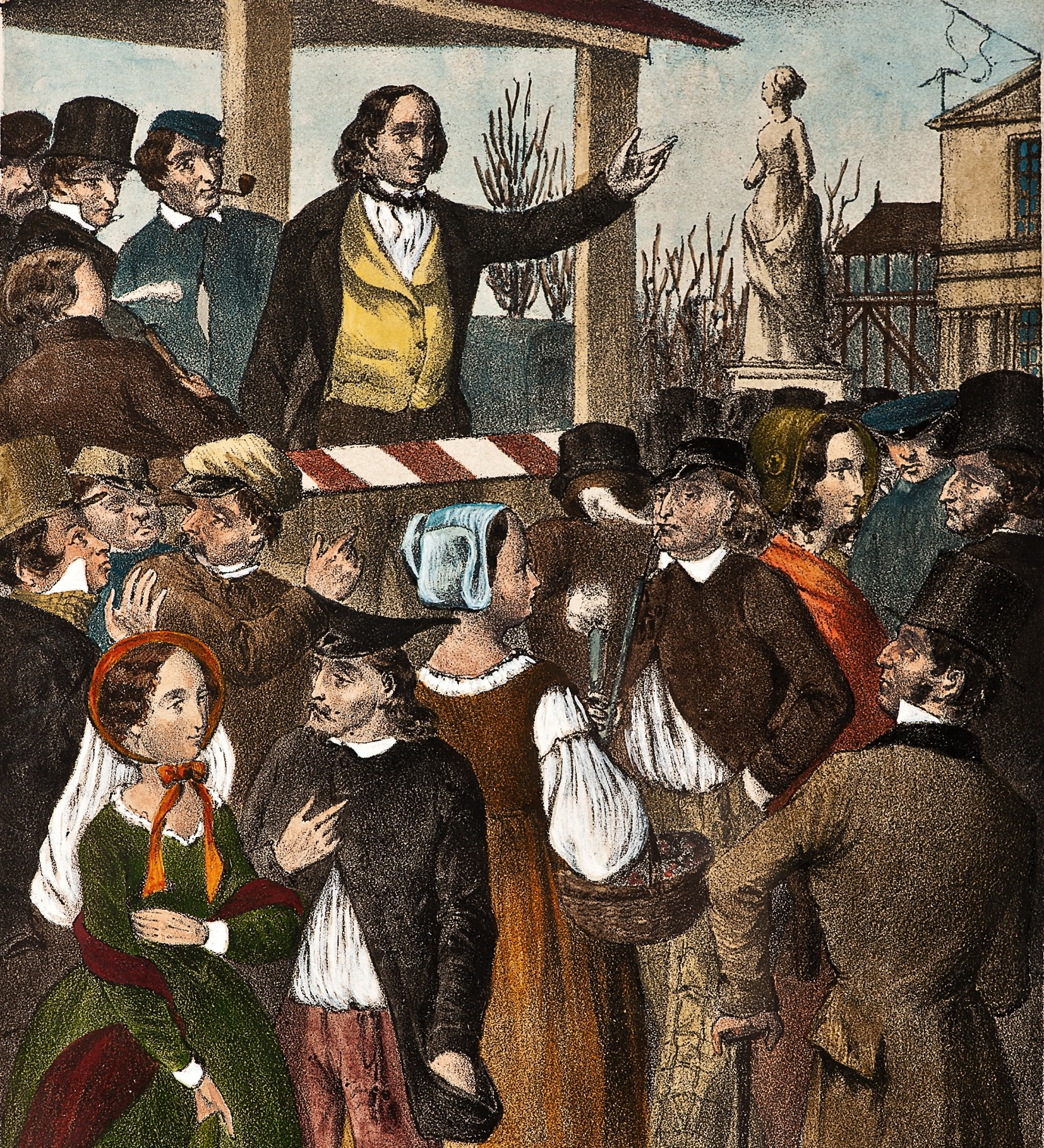

The revolutionary public of 1848

Image information

© Sammlung Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin

In February and March of 1848, demands for freedom of assembly, speech and the press were unleashing revolutionary upheavals throughout Europe. A wave of uprisings for democracy and civil rights started in Paris and Vienna, then moved to Berlin.

In early March ever larger crowds in the Tiergarten park were calling for reforms. They finally compelled King Frederick William IV to make concessions. On 18 March he granted freedom of the press.

This meant that everyone could now publish their political opinions in newspapers as well as in the form of leaflets and posters on walls – the latter known as Maueranschläge. Many posters were printed and affixed to fences or buildings, and were the object of great interest and intensive discussion.

Image information

Pressefreiheit in Berlin 1848, Lithografie von Vinzenz Katzler, 1850.

Two factors played a major role in the success of these printed products. The first was the introduction of high-speed presses which used new rotary technology to print a very high number of items in a short period of time. Not everyone had enough money for these projects, but high-speed presses lowered the costs. The second factor was public posting. Literacy rates were still low, but texts posted in public spaces could be read out loud, thereby reaching quite a few people and prompting immediate political discussions.

Image information

Meinungsfreiheit bei der Volksversammlung im Berliner Tiergarten 1848, Lithografie von Anton Ziegler, 1850.

This was an unprecedented way of spreading information. The posters provided new political content on a daily basis, and their public quality encouraged responses and discussion not unlike today’s communication on social media.

The posters reveal the political turmoil at the time, as well as the relations between workers, the middle classes, the military and the king in the struggle for democratic participation and against an absolutist state. The publishing information on each poster is usually a good indication of its political leanings.

The ability to freely publish political statements ended in Berlin on 13 November 1848 with an announcement that printing and disseminating posters would now require permits from the police.

The Documents collection of the Stadtmuseum Berlin contains numerous posters, flyers, leaflets and publication inserts from 1848 and 1849. Most of them consist of paper printed on one side. Replicas of some objects in the collection are displayed in the Revolution room of the BERLIN GLOBAL exhibition and given context here in the online collection. The explanations show how public prints during the revolutionary period were used to spread information, misinformation, propaganda, political statements and calls for gatherings and elections, but also for humorous and satirical purposes.